Stable Handling

- Atleta de Aventura

- Jan 4, 2022

- 7 min read

Keeping the canopy just over your head

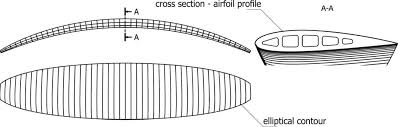

I don't usually talk about basic piloting, nor about flight safety procedures, which I consider to be content for SIV courses and basic instructors, and also something that is better used within the respective courses, which are differentially practical. In my POV, the perfect assimilation of what is experienced in the basic course or in an SIV takes place in the day-to-day flight, in-flight experiments, in conversations with friends before and after the flight and with additional reading about piloting techniques. So, here's a little more for your reading. Flying a paraglider is basically managing pendulums. We fly suspended by lines connected to a flexible airfoil. This airfoil suffers deformations due to some situations found in flight that cause it to gain or lose speed in certain moments and, in those moments, the moment of inertia is caused and the whole pendulum thing starts. Our body and harness account for more than 90% of the total weight of our flight mass. Imagine that the pilot weighs 80kg and is flying an Ozone Delta 3 ML paraglider with a Gin Genie Lite 3 M harness and an Independence Ultra Cross 125 reserve. There will be 80kg, added 11.44kg (5,440g + 4,800g + 1,200g), with another 5kg of clothing, backpack and electronics and, finally, with another 1kg of water, totaling 97.44kg. Of the 97.44kg of flight mass in the example above, 94.4% (92kg) is suspended from the paraglider in flight and by a flexible suspension. So, memorize: 1. The pilot and harness is a fine example of the heavy, solid body of a pendulum; 2. This heavy and solid body has a very relevant mass in relation to the pendulum figure (+90%); 3. Flexible suspension does not have considerable strength to attenuate the moment of inertia (delay the pendulum start moment); Let's look at the figure below:

In the picture I highlight what our standard flight envelope would be and also what tends to happen when we take the paraglider to the real flight scene, the atmosphere. Remember that there is no real fully stable atmosphere predictability during the day (7am to 6pm), which I call theoretical. What we popularly call a stable atmosphere is usually when there are no productive thermals.

In cases of paraglider deceleration, when we feel the sail falling behind, the correct procedure is to raise your hands so that the airfoil gains a little more ability to penetrate the air and tends to return to its normal position (over our head). If, at the time of this deceleration, by chance we already have our hands in the maximum acceleration position (trim speed), there won't be much to do but wait for the pendulum to start, with our body going forward and then returning, tending to cross the vertical axis of the paraglider, and the paraglider advancing to react to this pendular movement. The pilot must act on the brakes progressively, while the paraglider advances over our head, and the peak of this action must occur precisely in this position with immediate release in a symmetrical way (both brakes at the same time). In cases of paragliding accelerations, when we feel the sail moving forward, the correct procedure is to lower the hands, gradually and proportionally, so that the airfoil loses speed, and even is mechanically contained, and tends to return to its normal position (over our head ), when we release the brakes. If, at the time of this acceleration, by chance we already have our hands in a limit position for actuating the brakes, we must quickly assess whether the advance has energy or not. If the advance doesn't have energy, just keep the position of the hands and wait for the paraglider to return to the normal position. Now, if the advance has energy, believe me, the pilot should overact the brakes to contain the advance. If the paraglider threatens to stall, the pilot must release both hands quickly and symmetrically and immediately resume action quickly and determinedly. It is worth remembering that, in the day-to-day flight, what usually happens are small decelerations and advances of the paraglider, which are only managed with prompt action on the brakes without exaggerating the extension of the commands. Avoid being counter commanding the paraglider, which can increase the pendulum. In the image below I describe a slightly more active scenario that we can find in the atmosphere.

Note that I always draw the paraglider in a forward situation in red. Yes, this means that it is the situation that poses the most risk to pilots and that, unfortunately, they are the ones that most end up in a more complex situation or even in an accident. I think that pilots end up internalizing some rules for the limit of actuation on the brakes without, however, evolving this technically into the issue of handling dynamics. The brake limit that we must respect with the sail above our heads, without the existence of a pendulum, is less than the limit that we can explore when the sail is advancing over our heads, when we enter the beginning of a pendulum. Due to the greater speed, in the acceleration of the airfoil at the moment of advancement, we can, yes, act FAR MORE on the brakes to contain this advance. When the pilot lets any of the above situations turn into a pendulum and even lets the advance reach the point of a symmetrical or asymmetrical frontal collapse, it is a clear and unmistakable sign that that pilot has not learned to fly properly and/or is unsafe to act on the brakes of his paraglider. Below I will demonstrate now a slightly more complicated situation, when a pendulum starts due to a symmetrical or asymmetrical collapse.

When the paraglider suffers a symmetrical or asymmetrical frontal collapse, the airfoil immediately deforms and undergoes a great aerodynamic blockage, which abruptly reduces its speed and then starts the entire pendulum scenario. The big difference in this pendulum scenario is that the deceleration of the airfoil is more abrupt and, during the collapse, there is a large increase in the useful wing load on the paraglider (since the closed part is not flying or supporting anything). This sum of the greatest intensity of the moment of inertia and the greatest wing load at the moment of the pendulum is critical and requires a greater precision of time and response intensity from the pilot. In the case of a symmetrical frontal collapse (aka front), the pilot must place his hands in the magic position that he learned in school (ears height) and wait for the sequence of occurrences to, in due time, contain the advance. The pilot will wait for the typical drop, the paraglider will lag behind the pilot's vertical line (proportional to the intensity of the collapse) and, normally fully open, will use its natural tendency to fly again, added to the extra tension of the pilot weight (proportional to the drop - sometimes does not occur) to advance over the pilot. The pilot must, at the beginning of the advance, when the paraglider is still behind in relation to its vertical line (of the pilot), start acting on the brakes progressively and persist until containing the sail, remembering what was previously instructed to avoid an involuntary stall . In the case of an asymmetric frontal collapse (aka collapse), the pilot must immediately assess whether there is a tendency to turn, as he learned in school, to contain the turn with proportional action on the brake on the opposite side of the collapse. It is worth remembering that paragliders with high aspect ratio do not support great containment of the turn and the pilot must dose his hand more in this hold, not being so worried if any tendency to turn persists after maximum containment with the brakes. The important thing is, almost simultaneously with the containment of the turn, to act quickly and properly also in the reopening of the collapsing side. The greater the collapse, the faster the reopening action must be and the lower the tolerance to containment of rotation with the brake. Stay tuned for it!

Once the collapse is recovered, it is a matter of waiting for the sequence of events to, in due course, contain the advance. The pilot will wait for the start of the typical paraglider advance, generated by the natural tendency of the canopy to get back to normal flight and added to the extra tension of the pilot's weight, and must start acting on the brakes progressively and persist until the canopy contains, remembering what was previously instructed to avoid an involuntary stall.

Important Details: 1. During the advance, the further ahead of the pilot's vertical line the paraglider advances, the more brakes you need to use to contain this advance; 2. When having the paraglider behind its vertical line, starting an advance, the more precisely the pilot acts, the lower the advance will be; 3. The further behind the paraglider is in relation to the pilot's vertical line, the less brake it accepts; Tips: 1. Get intimate with your paraglider's brakes; 2. Don't be afraid to use your paraglider's brakes to contain advances; 3. In asymmetric collapses, try to contain the spin, but don't panic if any spin still occurs. The important thing is not to spin with speed and acceleration, that's all. And don't forget to reopen the collapsed side. 4. In extreme cases (minimum height and aggressive advance) it is better to stall the canopy than to risk crashing into the ground at maximum pendulum acceleration.

Author's Personal Note: In 2003, in Valadares, flying with Dynamic AR, I suffered an asymmetrical collapse approaching the landing on the side of the highway and the sail reopened facing the power lines. I decided to deny it, so as not to hit the wires. I put my hand full in, the turbulence hit again, the canopy spun without failing and began a dive. There was no time for anything, my body was as high as the wires. I didn't miss a second: I stalled the paraglider, which returned over my head in a horseshoe style, and managed to descend vertically from an approximate height of 2m. I hit the ground with my hands locked down, which gave me a mild injury to my left elbow and a visit to the doctor. As good as it gots!!! This reaction was only possible because I have some golden rules engraved in my mind for some cases and this is one of them.

Comments